A fair number of people in track & field were saddened by the death of Al Franken. I wasn’t. I was angry.

I was angry because Franken’s obituary was the first time I had ever heard his name and learned of his accomplished career in and contributions to the sport. I was angry because, let’s be honest here, if I did not know who track & field’s Al Franken was, few if any people of “my generation” working in the sport today knew who he was either. I was angry thinking about how much knowledge, insight, lessons learned, relationships and hilarious yet useful stories we lost last week – things this sport desperately needs to know as people attempt to do for track & field in the 2020s what Franken did from the 1970s through the early 2000s.

I was angry thinking about how much of my own effort and thinking could have been improved had I known about Franken early enough to ask around for an introduction so I could hear things from Franken himself, and get to know him for whatever time I could. (Among the many things I’ve learned, if you want to learn something useful about track & field – if you want to discuss actual innovation and smart business practices – find a septuagenarian.)

Many of the obituaries talked about how Franken was banned from the alphabet soup of TAC/AAU, essentially (perhaps literally) laughed in their faces and continued to hand bags of cash to athletes after his meets.

A familiar name that went along those stories was Ollan Cassel. Now that’s a name I definitely heard early and often in my track & field career. Pro athletes, activists and others told me all about Cassel’s back-stabbings, political maneuverings and power consolidations. He didn’t so much have a legacy but a continuing presence over so many of the attempts by track & field’s athlete-activists and donors to “do something” with the sport in the early 2010s. Even people who came into the sport well after Cassell stepped down from day-to-day roles talked about Cassell as if he was still the maker-breaker of any endeavor.

Yet no one ever mentioned the name of a man who didn’t waste his time standing up to Cassel, but simply side-stepped all such administrivia, did what he wanted to do, no permissions necessary nor desired, and succeeded by every measure.

That captures so much about the people and culture of track & field. They know every org chart, by-law and gatekeeper going back decades, and stay strictly within those boundaries. Yet they know nothing about the innovators, business people and successes that necessarily exist outside of governance fiefdoms.

While other sports and successful industries talk about standing on the shoulders of giants, track & field doesn’t even know who their giants are. So how can they ever see farther than their faded past and empty present?

People in track & field today puzzle over the sport’s complete loss of popularity as a professional spectator sport over the last 40 years. They look at what track & field had then and compare it to what it has now, and ask why then and why not now. Ultimately, track & field was popular in the past because, in the past, it had Al Franken and others like him. It’s not popular now because it no longer has people like Al Franken, and the people it does have don’t know who Franken et al were; and, even if they did, it’s unlikely they would try to learn from them.

MORE: TRACK & FIELD NEEDS SPORTS BUSINESS PROFESSIONALS, PART II

How can I make such a statement so confidently? Because every time I talk to someone from Franken’s generation – and, thanks to a friend and mentor, I’ve been able to talk many but not enough (I did miss out on Franken, after all) – they ask me who else from my generation is asking such questions and having such conversations, and lament that I’m the first such call they’ve received in, well, a long time.

Like any successful entrepreneur, Al Franken was a man of his times.

The lesson to take from him is not how to put on a track meet, any more than a tech startup today should study Steve Jobs or Steve Case to figure out how to build an Apple II/e or AOL Instant Messenger. Indeed, most of the attempts to re-popularize track & field are copy-paste’s from the playbook of the 70s and 80s.

We should instead try to understand how Franken captured the market as well as he did, how he met the fans where they were. We should dig into what he learned from his day jobs with pro golf, tennis and a startup called the Los Angeles Lakers. Right there are two easy lessons: have a day job and, better yet, have one in another sport to build your breadth of experience. We should find out how he convinced the athletes to join him in flipping the bird to Cassell and the TAC/AAU axis of useless, given how risk averse pro T&F athletes are these days, even when offered cash. We should explore the modern versions of what he did in each aspect of his operations. His meets incorporated the contemporary best practices of marketing, sponsorship, media and fan experience. Track & field was a leader in the sports industry then – the sport should look to the leaders of now.

START HERE: WHAT TRACK & FIELD CAN LEARN FROM VILLAREAL’S EUROPA LEAGUE VICTORY

And what are the timeless things he did that need no translation from the 1970s to the 2020s? His ability to recognize who and what are actually important, his happy warrior stance and open relationship with the media are a few low-hangers.

These are all the sort of things I would have talked to him about had I known who he was before he passed away last week.

RELATED: RETIRED EXEC’S CAREER EXPLAINS A LOT ABOUT TRACK & FIELD

Hopefully, I’ve made you some amount of angry and sad to think about what the sport lost because we let Franken take so much with him. As always, the parting question is: What will you do about it? Or, more precisely: What are you going to learn – and from whom - while we still can?

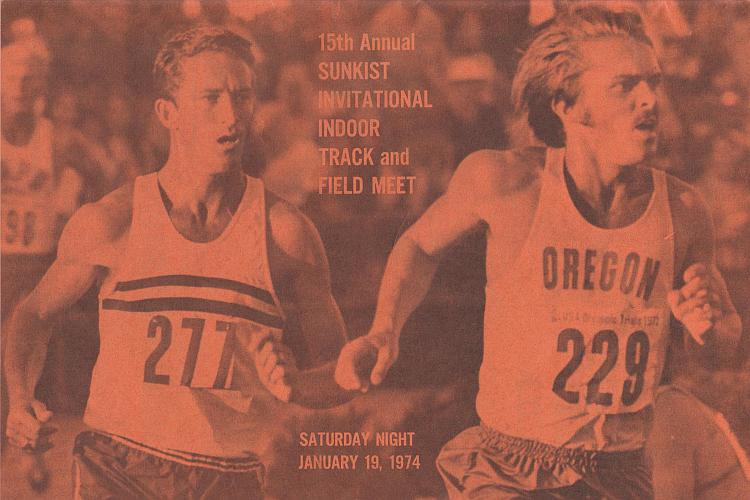

Photo credit and much other credit: The Sports Examiner