The NCAA likes to come back to their line that all but 2% of their 400,000 student-athletes will go pro in something other than sports. It’s a good line, especially when they are trying to put the spotlight on their support for all student-athletes instead of their exploiting a few for billions of dollars. But it should have been a warning to those sports who outsourced player development to the collegiate system.

The American college athletics system (not just the NCAA) is the de facto development pipeline and minor league for most American sports.

This leaves the collegiate system and the professional sports leagues and governing bodies in a classic mismatch of skin in the game; and, in the case of track & field, a potential collapse of development and mid-tier opportunities.

Collegiate and governing body spending on track & field

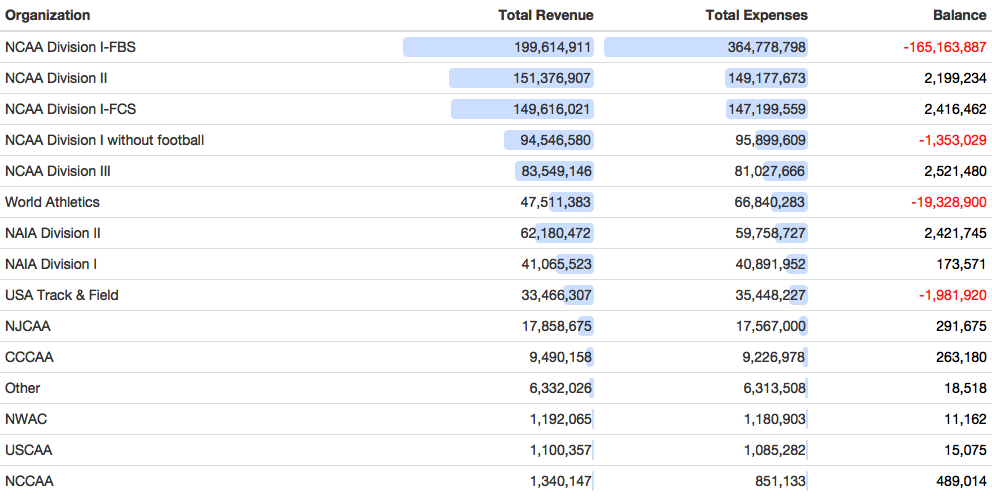

In 2018/19, NCAA schools spent $755 million on track & field and the NAIA spent just over $100 million. Toss in various junior college associations and a few independent associations, and the entire collegiate system spent $975 million on the sport.

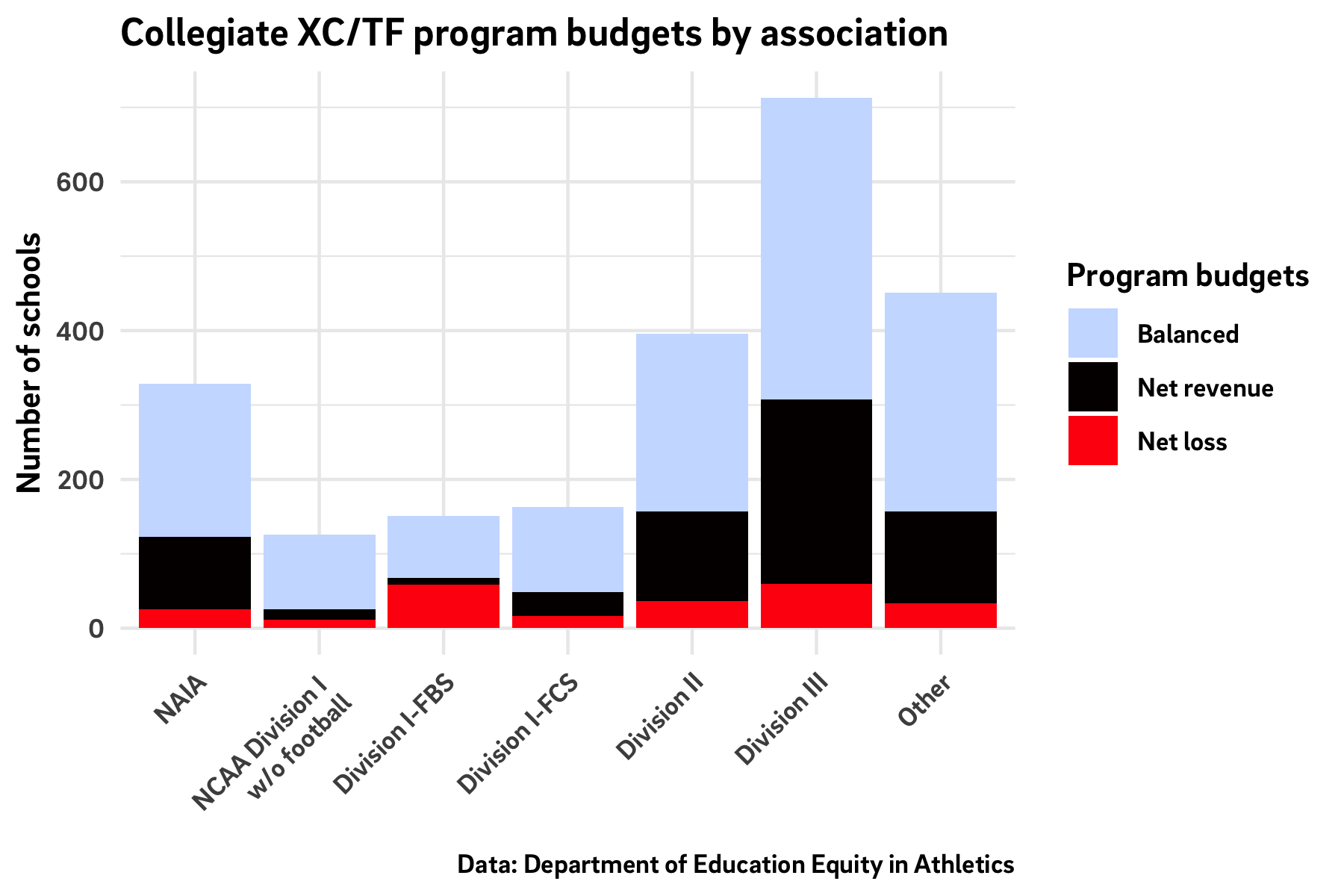

The NCAA came out $158 million in the red for track & field that year, while the entire collegiate system lost $156 million, showing how the NCAA is not just the biggest spender, but the biggest, well, loser on the sport. Actually, that’s not fair to Divisions II and III. They both stayed in the black. NCAA Division I - FBS lost $163 million, and Division I schools without football added a slight deficit of their own.

Stop and compare that to all the noise - some positive, most negative - around the 22-year, $500 million sponsorship contract Nike and USA Track & Field signed in 2014. That contract would not cover four years of the NCAA’s (or just D-I’s) losses.

At the school level, within the NCAA Division I - FBS, 51% of track & field programs operated with a balanced budget in 2018/19 and 42% took a loss on their overall track & field expenditures.

That leaves seven schools generating net revenue from track & field: a combined $2.5 million.

Meanwhile, 47 track & field programs lost more than $1,000,000 for the 2018/19 season. Not surprisingly, those 47 schools read like a list of the most famous and successful track & field programs.

At the 2018/19 NCAA Division I Outdoor Track & Field National Championships, 18 schools were represented in the top 13 for either men’s or women’s team scores. Five of those schools - Brigham Young University, Florida State University, Mississippi State University, University of Houston and University of New Mexico - had a balanced budget for the year. All the rest operated at a loss - a combined loss of $46.7 million.

NCAA Division II and Division III lead all collegiate athletics for having the most track & field programs in the black: about 36%. Only 9% of track & field programs in those categories took a loss, whereas in the NCAA Division I-FBS, an even smaller percentage - 5% - brought in net revenue. But Divisions II’s and III’s sound management is not a sign of parsimony: they spent $149 million and $81 million in 2018/19, respectively.

Let’s stop again and compare the collegiate system’s spending on the sport to the national and international governing bodies’.

Rich Perelman of The Sports Examiner reported USATF’s operating revenues and total assets for 2018 were $34.5 million and $39.9 million, respectively. They couldn’t even cover the losses - again, not the expenditures, but the losses - of the top NCAA Division I programs, the very programs that are the biggest contributor of athletes and coaches to USATF National Championship events and the various national teams.

USATF CEO Max Siegel’s noisily derided compensation of $4 million is less than 12 individual schools lose in a single year.

A month later, Perelman - via an anonymous benefactor - reported some of World Athletics’ financials for 2018. The global sporting organization for track & field had $45.7 million in revenue and $68.1 million in expenses in 2018. Events and “sport development activities” accounted for $20 million of their expenses.

So, once more with feeling: the global federation for track & field took in as much money in 2018 as 18 NCAA Division I schools lost as a group. The United States’ federation took in less than that. Each component of the NCAA - Division I-FBS, Division I-FCS, Division I schools without football, Division II and Division III - and the NAIA spent more than World Athletics.

And, with the exception of Division I-FBS and Division I without football, they operated with positive revenue - unlike World Athletics.

Sources: Department of Education; The Sports Examiner; USATF

Where will track & field athletes come from - or go - as programs disappear?

One of the early lessons of the coronavirus pandemic was that companies and industries cannot rely on a single supply chain for a vast majority of their goods or inputs. This is the flip side of what every company already knows: you won’t survive if you only have one customer, no matter how big or monopolistic that customer may be.

Professional sports leagues and national governing bodies in the US passively outsourced their development systems and minor leagues. The colleges stepped in because largesse was feasible and fashionable.

Now it may not be.

Even if NCAA non-revenue programs come through the COVID-19 shutdown era mostly intact, athletes, leagues and governing bodies - those consumers of athletic development - should recognize the wake-up call. No one needs well-developed athletes in their prime as much as the leagues and governing bodies: they need either to put their skin in that game, or find a partner who will.

Across the collegiate system, track & field is the fifth-costliest sport in terms of total expenditures, but has the highest deficit. Football and basketball cost the most, and are the only two revenue-generating sports. Next are soccer and baseball. They both spend more than track & field, but their deficit is about half of XC/TF’s.

Baseball, soccer and hockey are the only team sports with extensive regional and minor league systems. This allows those sports to take in a large number of athletes post-college, sort them according to their skill level and provide a path to the top tier. But neither of them - unlike hockey in Canada and soccer in Europe - offer a path from youth to professional via parallel progressions through the age groups and league pyramid.

The path from youth sports to professional sports - major or minor league - for baseball, soccer and hockey is the same as football, basketball, tennis, golf, track & field and all the rest: they all go through the scholastic / collegiate systems, a system whose dominant force wrote a great marketing slogan around the fact that they are the final athletic destination for 392,000+ student-athletes a year.

We can’t fault the NCAA for that. But we should consider the risks and trade-offs of letting a dead-end system become the driver of American sports.

American track & field relies on the college system not only to develop athletes age 18-22, but to provide competitive opportunities for post-collegiate athletes.

Post-collegiate athletes seeking qualifying marks or simply half-decent competition compete mainly in college meets given the paucity of independent events. The situation is not much better at the top international levels: World Athletics spent $20 million on events and sports development, of which $4.55 million were for the Diamond League.

The athletes who will be most affected by XC/TF program cuts are those approaching or already in college. They will take the full force of the hit. They will lose their development pipeline and have nowhere to go. Those already on the small, unsatisfying circuit will stay on the small, unsatisfying circuit, and will be replaced by athletes coming from a smaller and, therefore, less competitive pool.

We know one person who will be happy about that.

Coaches will be pushed out, too. With fewer athletes and fewer jobs, the sport will have fewer coaches to maintain and expand the profession’s knowledge base.

Track & field and other sports are not facing new financial, player development or competitive threats because the COVID-19-induced shutdown is jeopardizing football revenues. They have been living under these risks for decades because, as cultures devoid of entrepreneurship and as federations content with an affordable status quo, they were content to let someone else spend a lot of money doing (part of) the work that they would otherwise have to.

Over the next 10 years, the effects on the sport will reveal themselves.

The COVID-19 shutdown didn’t cause this predicament. It’s just what came along to do the trick.

Photo credit: Shiroyama Athletics Stadium, Tagosaku / Flickr under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)