Track & field does not make it easy to know who - or what - a professional track & field athlete is. National championship meets are more likely to surface students, side hustlers and ambiguities than an unequivocal pro.

Track & field loves its information gaps when it comes to money and professionalism. The assiduously guarded secret of athlete sponsorship contracts - the existence of many of which are revealed only when the sponsor’s name appears next to the athlete’s on a heat sheet - protects both parties from having to admit how little the contract is worth. Athletes who receive only kit end up with the same identification as those making a full-time living, and that’s just as well for all involved, except for the fans and watchers who may want to know more, but when have the fans ever been a consideration?

After our blog on collegiate track & field spending did the rounds, we saw a question in a Twitter thread asking how many collegiate athletes go on to become professionals.

With no information about how much any athletes make, there’s no direct way of knowing how many athletes could be considered professional or semi-professional.*

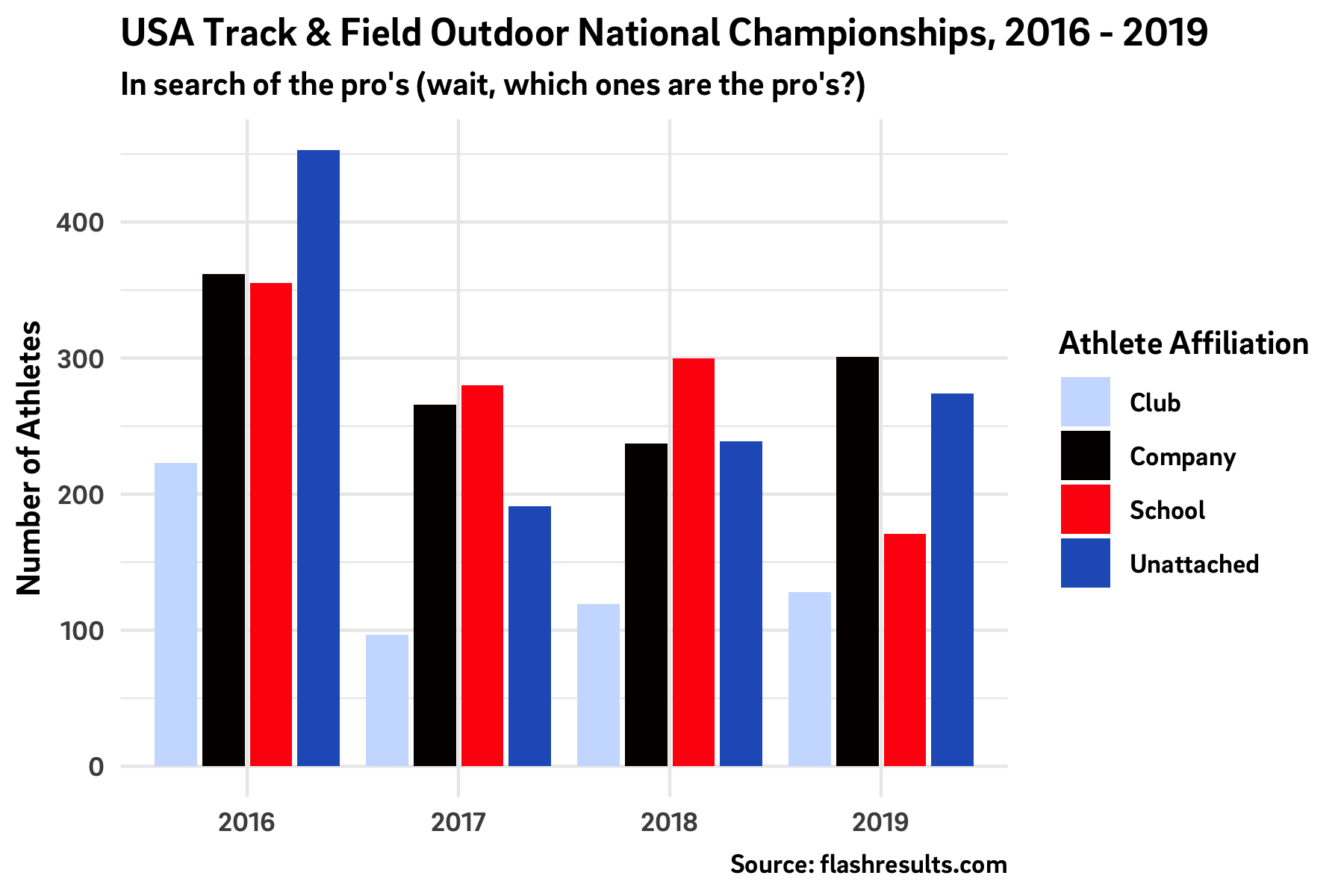

As a proxy, we pulled down the athlete lists from the last four USA Track & Field Outdoor National Championships (2016 - 2019). We parsed their listed “affiliation” into four categories: company, school, club and unattached.

Athletes who listed any company name or service branch in their affiliation fell into the first category. These were 18 shoe / apparel companies, the U.S. Army and the U.S. Marine Corps.

Unattached were easy. They say what they mean. We hate the term, but that’s for another time.

To identify the club athletes, we made a list of “club words” and phrases, such as “project,” “T.C.,” “distance,” “speed,” etc., working our way through until there were no more non-schools left among the affiliations. Everyone left, therefore, represented a school.

Of the four USATF Outdoor National Championships we looked at, in only one - 2019 - did companies have the most affiliated athletes. They did so by a much smaller margin (27 athletes) than those by which unattached and school athletes led in previous years.

Let’s note here the importance of thinking of these athletes as “company” athletes and not “professional” athletes.

Between the known unknown of how much any of them gets paid and knowing that some of them list a sponsor that only provides limited kit, our methodology overstates the relationships between companies and athletes by including club-level sponsorships in the “company” count. If a sponsor’s name shows up with the club name, that athlete is counted as a “company” athlete even if they have no individual relationship with and receive nothing directly from the sponsor.

For all we know, they might not even receive anything beyond a jersey from the club. What you see in the graph above and discussion below is a significant overshoot of how many of these athletes are pro’s.

Aside from not moving us any closer to determining who or what is a professional track & field athlete, the USATF Outdoor National Championships roster reinforces just how much the American college system - the NCAA in particular - is the driving force in American track & field.

College athletes were 28% of the total competitors from 2016-2019. Over these four years, only 60 more company-affiliated athletes - the closest thing we have to “professional” - competed than collegians. Consider that college athletes are all in a four-year age range, whereas company-affiliated athletes cover at least twice that (on the to-do list: age distribution).

At least the NCAA schools are getting what they or their benefactors paid for.

These numbers raise two factors from a market perspective: the limited market capacity for professional track & field athletes, and the desire among post-collegiate athletes even in the absence of “professional” opportunities.

Company-affiliated athletes made up 40% of the post-collegiate competitors. Most of them are out there for very little money. The other 60% are out there for even less (as in, none).

The pertinent question is what is really driving those 60%, along with those who fell short of qualifying for these meets and - for our purposes - those who were nowhere close to the qualifying standard but are still in a throws circle, on a runway, over a landing pad or around a track several days a week.

Is their ambition to someday become a company-affiliated athlete? Do they want to be professionals - however defined in whatever structure - in track & field / athletics? Or is competing at a national championship an end in itself, a more competitive version of a participant medal but one with not much athletic, professional or financial ambition beyond that?

That’s what we need to know, so if you’re one of the 60% or one of the roughly 30,000 track & field student-athletes who graduate and leave the sport every year, drop us a line. We will literally (literally!) talk to each of you, and maybe we’ll do a group Zoom or podcast to hear and share what you have to say.

*For what it’s worth, we consider a professional athlete to be anyone who makes their full-time living as an athlete. Athletes who rely on family support in order not to have a day job don’t count. A semi-pro athlete is anyone who gets some value from sponsorship(s) or competition, but has to work a day job to keep the lights on.