Basketball has Adrian Wojnarowski. Soccer has Fabrizio Romano. Football has Adam Schefter. Track & field has no such person and, if some pro athletes and a large part of the fan base has their way, never will.

The summer transfer window is the holiday season for soccer writers: if you can’t grow your audience and hit all-time highs for page views between July 1 and opening day in mid-August, it doesn’t matter what you or your team during the season. You’ve underperformed, and you’re going to have a down year. I learned this during my first summer covering Chelsea FC, and it never stopped surprising me in the subsequent four years.

The rumors and leaks about which teams will buy and sell which players for how much are the raw materials for the soccer content industry. And it is an industry. It’s big business, even if very meta: the business of the business of soccer.

Other sports have this to a lesser extent. The confined nature of the NFL and NBA limit the possibilities for where a player can go; trades don’t have a dollar amount attached to them, even if they represent similar exchanges of value; league policies like salary caps put a ceiling on how blockbuster an acquisition can be; and, for these and other reasons, even the wealthiest team owners can only do so much to drive player recruitment, unlike in European soccer. But even so, Adam Schefter and Adrian Wojnarowski have built their careers on accurately sourcing, revealing and predicting imminent player moves.

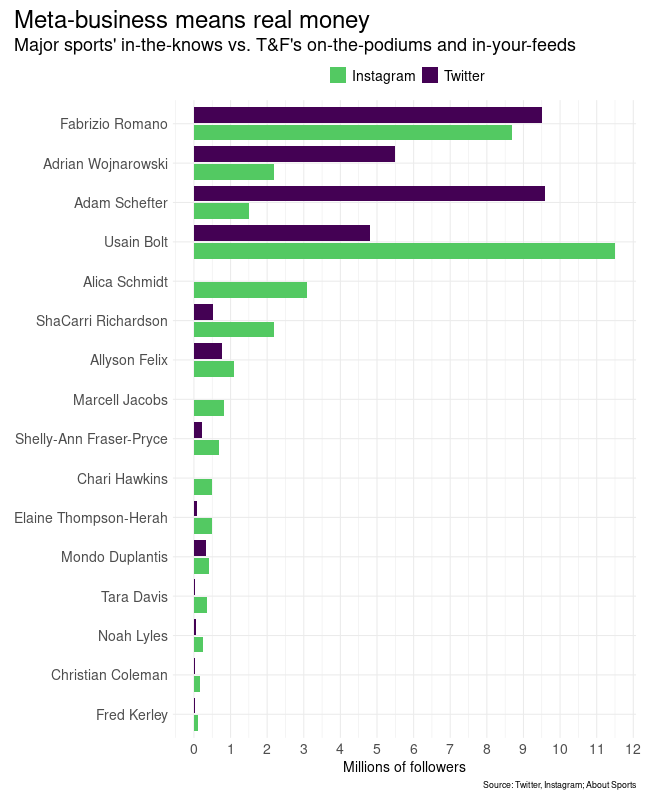

The chart below compares the Twitter and Instagram followers of Schefter, Wojnarowski and soccer’s Fabrizio Romano with some of track & field’s most popular or successful athletes.

These reporters have more followers than nearly all track & field athletes. More than Olympic medalists, more than NCAA champions, more than people who look much better in your feed.

They also make a lot more money. Earlier this year, ESPN renewed Schefter’s and Woj’s contracts to pay them each over $10 million per year for the next several years. Fabrizio Romano is a freelancer, so there is no information or rumors about how much he makes. But he regularly appears across global sports media, his podcast is sponsored by fan engagement company Socios and clubs have hired him as part of their transfer announcements, given his renown and recognition, and that of his catchphrase, “Here we go.”

We obviously don’t know what track & field athletes make, but we can confidently say it’s less than $10 million a year.

OTOH: WE DO KNOW WHAT MANY COLLEGE TRACK & FIELD COACHES MAKE

Last week, track & field had what seemed to be a credible contract rumor, the kind that fuels the meta-business that has Romano, Shefter and Woj at the top of their field and a pile of money. Kenny McDaniel, director of track & field and cross country at Sacramento State, tweeted that University of Kentucky’s Abby Steiner had gone pro with a $2 million contract from Puma. The replies and quote tweets were overwhelmingly positive. Some were skeptical, given the opacity of track & field contracts and the lack of any clear connection between McDaniel and either Puma or Steiner. But people were happy for Steiner and for the sport, were happy McDaniel put it out there, were hopeful it was true and shared it accordingly.

Abby Steiner herself ended the positivity and so-much-like-a-successful-sport conversation the next morning. She said, in part, “[P]eople trying to leak my deal and contract have been some of the most invasive and bothersome narratives I have seen. This information is between my sponsor and me. Any source outside of that is simply speculation.”

True. Unless McDaniel has a well-placed source at Puma, it is simply speculation. So are many (most?) of the articles, tweets and podcasts that drive millions (billions?) of impressions and millions of dollars through soccer, football and basketball every year. So are all the articles, tweets and podcasts – similar in volume and financial return – about who will be in the starting lineup for this weekend’s game; about whether the new manager will use a 4-2-3-1 or a 3-4-3 system, and what that means for players in the squad; about whether the star player or the coach of a struggling team will be first to go.

These speculations are the business of sports fandom, just as much as ticket sales, broadcast viewership and merchandise sales.

Steiner also said “As a reporter, it is your job to fact check… It is common knowledge that contracts are not public.” Well, yeah, we know. That’s part of the problem, and it makes it impossible to fact check any rumors.

Not one former or retired pro track & field athlete has ever posted or otherwise disclosed their contracts, not even with you’ll-never-find-me redactions. Imagine what those speculations would be like, as everyone tried to figure out whose contract it was and who leaked it. Nor has any former agent or shoe company employee ever pulled back the curtain on the process or contents of track & field contracts. Not the ones who soapboxed about transparency while they were competing, and not the ones who claim to represent something different in this space.

Steiner is inadvertently making the case for another benefit of contract speculations and rumors: they drive transparency.

She said it’s a reporters job to fact check. Fact check: true. If there was more in the sport to report on, more facts to check, there’d be more reasons for more reporters to text or call the people they know at the shoe companies or agencies to try to get some off-the-record or background information. Reporters would develop sources, building trust with brand managers, agents, athletes, coaches and – through that trust – with their audience, the fans (Schefter apparently spends $16,000 a year on chocolates for his sources). Those reporters who scrupulously protect their sources and just as scrupulously report and caveat on what they hear would rise to the top. Not Romano-Woj-Schefter levels in absolute terms, but certainly to those levels in relative track & field terms.

The replies and quote tweets on Steiner’s tweet were overwhelmingly supportive. They, too, thought the conversation around the speculation was dirty and wrong and a distraction and an insult. Placed alongside McDaniel’s tweet, they show two camps within the track & field fan base.

Every athlete, celebrity or other public figure has their way of dealing with the media machine: ignore, engage, outsource, delete. If they choose to engage, the whole spread from amiability to attack – if done well - can be beneficial to their brand. I believe that an athlete can be completely absent from social media without harming their earning potential. Even in individual sports, I think social media is an independent, parallel revenue stream, not an inseparable component of their main revenue stream.

But what an athlete and fans cannot do – logistically, practically and financially – is try to stop the conversations around and about them (see also: Richardson, ShaCarri). Because they are the sport. If people are not talking about the athletes, they’re not talking about the sport. If they’re not talking about the sport, the sport has no business. If the sport has no business, then we’re back to the beginning of the cycle: nobody’s talking.

RELATED: TRACK & FIELD CAN LEARN FROM TENNIS: NO MEDIA, NO MONEY

No group of fans or athletes should know this dynamic better than those in track & field.

The business of athletes getting paid gobs of money for their achievements satisfies two of the fundamental reasons why sports are what they are: entertainment and aspiration. The contracts and the checks are right up there with wins, goals, race times and any other on-field measure of success.

Fans convert athletes’ on-field achievements into the business achievements. That relationship starts the cycle by which the business of sports spins off a meta-business that further enriches those in the sport: the athletes, coaches, teams and leagues. Plus, it creates new revenue streams for a different set of people: media and content production. It’s a perfect example of something I’ve been saying for a decade: track & field doesn’t need to “grow the pie.” It needs to become a kitchen in which anyone can make and market pies, cakes, salads or entrees. Like every other sport has done for the last 20 years.

Ask the fans to remove themselves from this relationship, and they’ll give a collective “Here we go.” They did for track & field several decades ago, and there’s not much to lure or welcome them back.

As if to prove the point… as I was preparing to post this, I saw this article from a country where track & field very much is a successful professional sport. Checking out the Jamaica Observer’s Twitter feed, they had back-to-back posts about Elaine Thompson-Herah: one about her PB, her SB and her chances at World Championships, and one noting that she was wearing Puma shoes – not Nike – at the airport and speculating that she might be switching sponsors. The one about a potential sponsor change has four times as many comments and retweets, and twice as many likes.

Based on the engagement on McDaniel’s, Steiner’s and the Jamaica Observer’s tweets, track & field fans want more contract speculation and signing rumors. Kenny McDaniel has one quarter the number of followers as Steiner, yet his tweet was shared almost twice as many times and has 50% more likes. He clearly gave fans something they want. The sooner others in the sport do the same, the sooner and to the same extent will the fans be willing to send value the other way.