Athletes should react quickly. Institutions should not. Somewhere between Devon Allen’s reaction time and the pace of change in track & field is the appropriate speed for the sport to rethink its false start protocols to account for a honest outlier.

If any athlete was going to be wrongly disqualified for a false false start, it was Devon Allen. His reaction time data from across his career shows that being first off the line is kind of his thing.

We looked at data from 1,044 athletes (519 men, 525 women) competing in 436 sprint and hurdle races: 60m, 100m and 110m hurdles, and the 100m and 200m sprints. The meets cover eight USA Indoor and Outdoor Championships - including the 2016 and 2021 Olympic Trials - 10 Diamond League meets and four NCAA championships. Originally, we were only going to look at the races that Devon Allen competed in. We then added all sprint and hurdle races from those meets, and then added a few meets (the NCAA championships) that he did not compete in. We incorporated those additional races and meets to provide context, and maybe to take the edge off Allen’s perceived dominance: anyone can look good when you build your dataset around them, right?

But the more meets that entered the dataset, the clearer Allen’s reaction time freakitude (it’s a word) became.

Devon Allen: Reaction time GOAT?

Devon Allen had the fastest reaction time in 12 of his 28 races, the most of any athlete in the data. Just behind him, and with a better percentage, is fellow Oregon alum English Gardner, who was first out of the blocks in 10 of her 12 races. Behind Gardner were Tonea Marshall (10 / 13), Kayla White (9 / 18) and Aleec Harris ( 5 / 10).

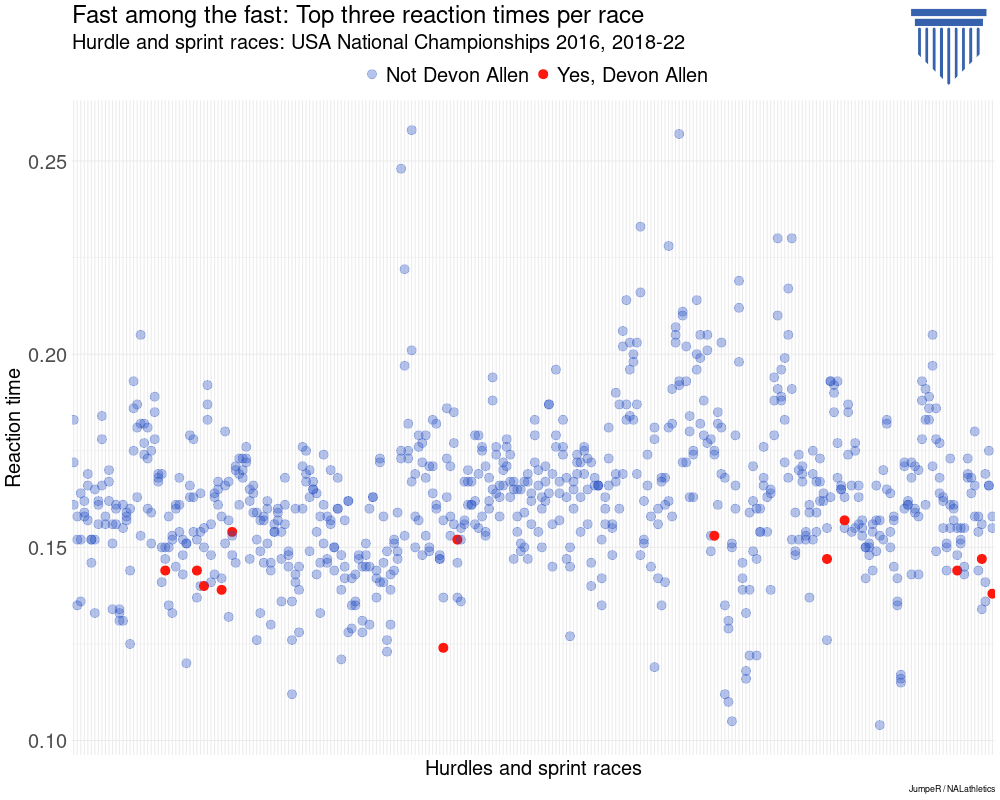

Allen’s average reaction time over those 28 races was .138, by far the fastest of the 59 athletes with 10 or more races in the sample. That average reaction time is also faster than the fastest reaction time of 846 athletes in our data. Tonea Marshall had the next best average reaction time at .145, then Michael Rodgers and English Gardner at .151. Allen and Marshall were the only athletes to have their average reaction time <0.150 from 10 or more races.

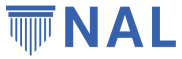

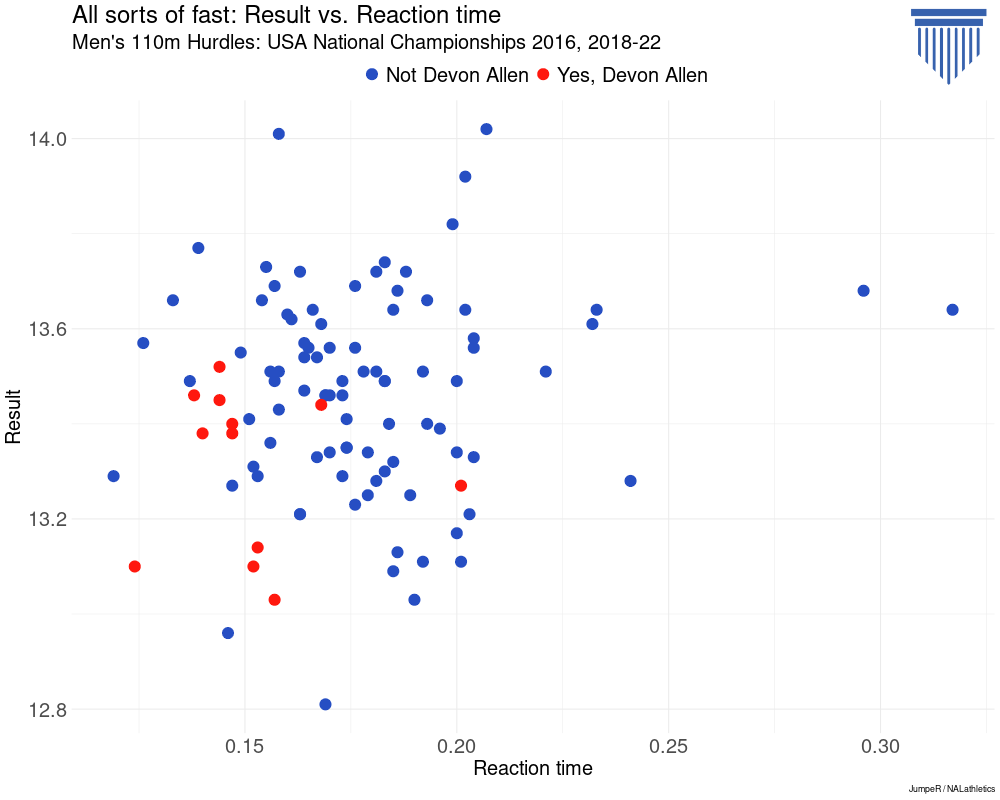

Allen managed this low average despite having a race with reaction time greater than .200: it was .201. The graphs below show that Allen is not just occasionally super quick to start, although he did share the fastest reaction time of this subset of athletes: .104, along with Keni Harrison. He is consistently one of the quickest reactors, and he’s quick even among the quick. Extract just the three fastest reaction times from each race, and Allen is still consistently quicker than the average.

From the full dataset, 361 athletes had at least one race with a reaction time under .150. Allen did it 22 times, while four athletes did it seven times and four athletes did it six times.

Likewise, 38 athletes took their reaction time under .120 at least once. Devon Allen had four such races. Shane Brathwaite, Mujinga Kambundji and Andrew Pozzi did it twice each; and all the others did it once.

Nothing “false” about Allen’s data: Reaction time is performance and strategy

The main caveat to this analysis is that it is thorough but not comprehensive. By only selecting US championships and Diamond League meets, we’re not able to examine trends across a season or over years. Since these are the most important meets of the year, it’s possible that Allen takes greater risks with anticipating the starting gun than he would during races with less at stake. The data here may reflect low risk aversion or high (accurate? Lucky-until-he-wasn’t?) anticipation. However, risk taking is a necessary component of any sporting endeavor: who dares wins, fortune favors the bold, and the like.

If Allen is more of a risk taker than his peers, then his streak ended at Eugene this past weekend. Conversely, if Allen is more of a risk taker than his peers, that goes a long way to explaining why he was competing at World Championships while on a contract with the Philadelphia Eagles.

Regardless of the root causes, Allen has spent his career consistently flirting with the threshold for a false start, yet he has never been accused or suspected of playing casual with the rules. He’s not the sprinting version of a card counter. His performance data shows that it was likely a matter of time before he was flagged for a false false start. Being at the limit of human performance, his choices were either trying to shave off a few (but dear god not too many!) thousandths of a second or sit back on his performance to ensure a legal start. Not that he’s not fast once he’s going over hurdles, but again, you don’t take time away from the NFL to compete in World Championships because you go through sport content with some of your performance metrics.

Let’s Run shared some interesting data on the median reaction times from World Championships over the last decade. Those graphs suggest that something was unusual with the timing systems at this year’s World Championships. Median reaction times across multiple events were relatively consistent, until plummeting to about half their annual levels this year. If there had been significant improvements in coaching and performance over time, the decline would have been gradual. And sprint starts seem to be immune to super shoes, the heart of so many eyebrow-raising performances this year, so we can rule out athlete tech.

MORE T&F DATA: NCAA Track & field spending and success: Can we buy a point?

That just brings us back to the singular athlete that is Devon Allen. He did not drop his reaction times significantly this season compared to previous years. If World Athletics did use a new (or misuse an old) technology in the starting blocks, it leveled the playing field and brought other athletes’ reaction times more in line with Allen’s usual. As often happens, levelling the playing field – intentionally or not – came at the expense of the high performers.

Photo credit: Phil Roeder / Flickr, under CC BY 2.0. Date credit: JumpeR, available on CRAN.