No one knows how much money track & field athletes make, but everyone seems to agree that they should make more. However, based upon the significant metric of average attendance per game (match, meet, what have you), track & field athletes may be out-earning their peers in other niche or minor league sports.

Yes, niche or minor league sports. Track & field athletes competing in the Olympics or World Championships are the athletic equivalent of NBA, NHL or Premier League players, just as they are also the athletic equivalent of the world’s best lacrosse, volleyball, netball, kabbadi and field hockey players. This latter group provides the better comparison for where track & field athletes stack up in the sports marketplace, as do the lower tiers and minor leagues of the Big 4 American sports and soccer globally.

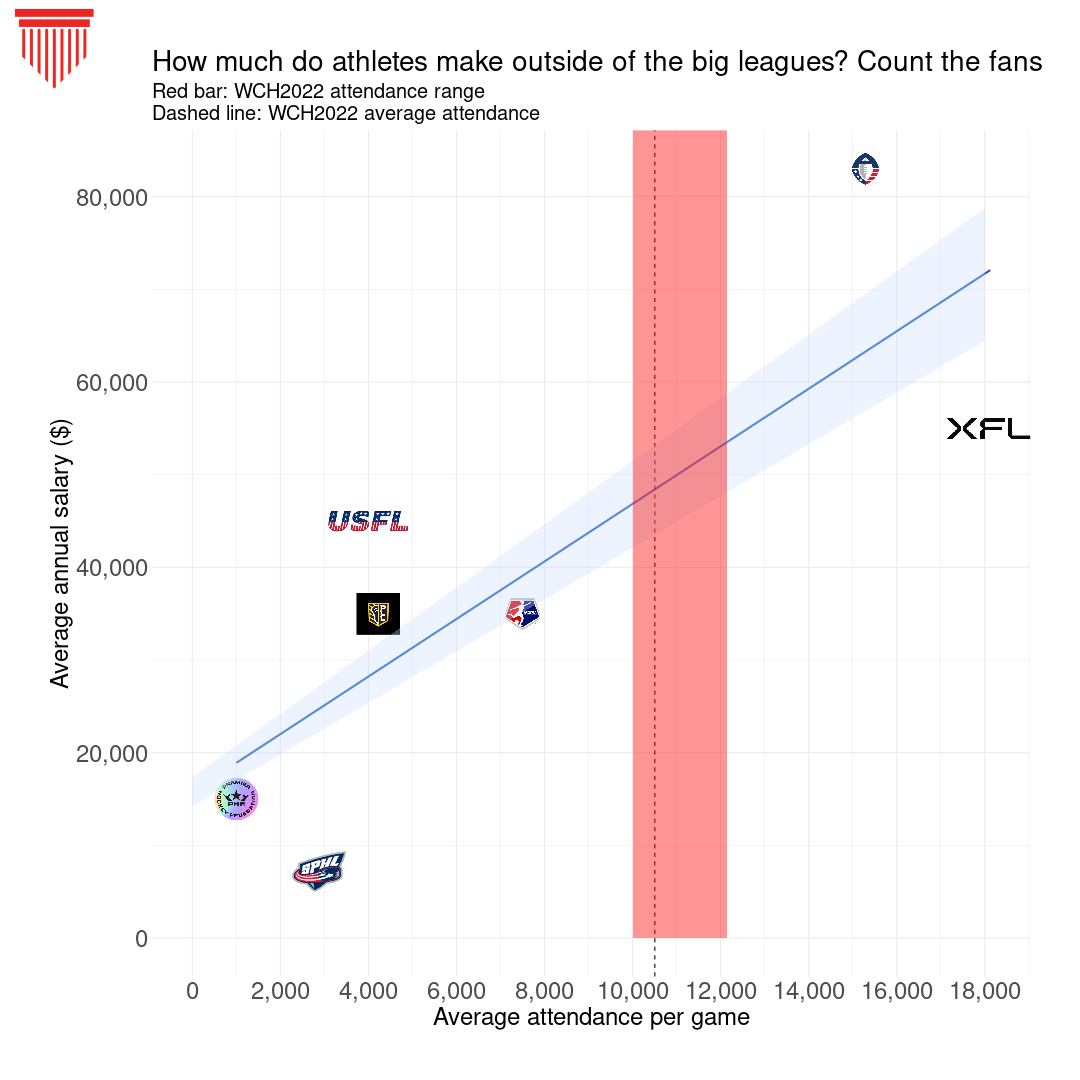

The dataviz below shows the average attendance per game and the average salary for seven non-major professional sports leagues in the US: the Premier Hockey Federation (top tier women’s hockey, formerly National Women’s Hockey League), National Women’s Soccer League (top tier women’s soccer), Premier Lacrosse League (top tier men’s lacrosse), Southern Professional Hockey League (independent far-from-top-tier men’s hockey) and three startup leagues in American football, the XFL, the Alliance of American Football and the United States Football League.

Actually, before the dataviz, let’s just pause to note that, with the exception of the USFL, all of this information on attendance and salaries either comes directly from the league’s public-and-easy-to-find data or major mainstream media (Forbes, ESPN, CNBC, etc). The Southern Professional Hockey League – the smallest of all the leagues here – even has a sortable table of attendance on their website, while the PLL – the kings of venture capital funding rounds – would do a short post of the attendance for each weekend’s matches. Funny thing, transparency.

That is a remarkably well-fit linear relationship.

Perhaps the only validated attendance data for track & field is from the 2022 World Championships in Eugene. Per-session attendance ranged from about 10,000 to a maximum of 12,143, with an average of 10,506, the shaded red section on the graph. Using the relationship from the graph above, track & field athletes should average $48,419 per year.

You tell us: is that, on average across all events, what the athletes at World Championships make in a year?

To the extent we can feel confident in assumptions and hearsay, we can feel confident in the assumptions and hearsay that sprinters and milers greatly skew the distribution of salaries, especially compared to the events like those that even World Athletics thought were too niche for comfort, triple jump and discus. In this regard, track & field salaries may have a similar distribution as the NFL or NBA, where a few players in a few positions open a huge gap between the median and the mean.

Among the leagues we’re focusing on, though, we know the minimum and maximum because – brace yourself, tracksters, this is where it gets weird – the leagues make it public. The PHF and NWSL publicly announced their minimum salaries and their salary caps ($10K/30K and $20K/$50K, respectively); while the SPHL publicized their salary cap ($5,600 per week per team). The three football leagues offered a standard base salary to all players, with different incentives based on whether a player played in a game, whether the player’s team won the game or won the championship. Similarly, an independent professional basketball league, The Basketball League, which is not part of the broader analysis because they do not have publicly accessible attendance data, have right in their FAQs that players will make $500 - $5,000 per week.

$5,000 a week. That’s a quarter million a year, right?

No, that’s $5,000 for each week of the season. That brings us to a critical contrast between track & field, and the attendance at World Championships, specifically, that we noted in a recent post, and all of these of leagues. Track & field averaged 10,506 fans per session for 10 days, in one city, in an annual, international event. Most fans attended multiple sessions, so the number of unique fans is probably not far off from this average number of fans. The number of unique fans is certainly closer to the average than it is to 10,503 fans * 13 individual sessions.

THIS ONE: Track & field did for one week what second tier soccer teams do every week

USA Track & Field National Championships likely put up similar attendance numbers, but under similar circumstances as Worlds, simply scaled down to the level of a single, massive country: annual championship event, single city, multi-session attending fans, large number of athletes. None of the independent meets in the United States come anywhere near these figures, and even if they did, they still happen once per year city, making them more of a special event than a part of a persistent, continuous sports presence.

Compared to all these other sports, which represent averages across time and space. The SPHL averaged 2,872 fans across 11 teams in eight states (only one of which is a true, traditional “hockey state) each playing a 56-game season. The team with the highest average attendance – 4,811 fans for the 2021-22 season is in Huntsville, AL, which, I can assure you, is not a Eugene-style HockeyTown, USA.

(Article continues below table)

<!DOCTYPE html>

Two of the leagues have non-traditional schedules. The Premier Lacrosse League holds match weekend carnivals, with three games in a single city over one or two days. The United States Football League went to the extreme of having all games for its 2021/22 season in Birmingham, AL. This created a significant gap in game-to-game attendances, with 10-15,000 fans attending the Birmingham team’s games – home team advantage, and all – while only 1,000 – 2,000 fans attended the others. USFL says this disparity was expected, planned for even, as they are building a streaming-first audience, with in-person fans being a lagging, secondary metric of interest.

In-person fans are, obviously, only one component of a sport’s commercial viability. All major sports have TV and streaming audiences that are orders of magnitude greater than their ticket buying crowds. Sure, if you were bored and looking for a hot take, you could argue that in-person attendance is an archaic KPI, and that digital-first audience building is the new hotness. If that was really the case, though, broadcasters and owned media would not put out the effort to frame their camera angles to make the stadium look and sound packed. And just ask the athletes what environment they would prefer: “Yes, you can hear a pin drop and nobody will be clapping you on and off the field, but the mobile numbers are amazeballs!”

What does this mean for track & field athletes’ pay?

Track & field needs more of everything, everywhere

For athletes, fans, properties and everyone with a financial interest, in-person attendance is and will remain a primary metric of a sport’s success. That means it is upstream of many other decisions and outputs, including player pay.

If people want track & field athletes to make more money, they don’t need to look for more ways to get more people to attend USAs or Worlds or the Olympics. They need an everything everywhere but not all at once, spread out over 6-8 month season approach. Two thousand fans at each of 30 events across six cities has greater commercial viability than 60,000 fans for a weekend, not that track & field is getting 60,000 fans on a weekend. That would be the most effective and sustainable way to move track & field athletes up and to the right on the curve their peers in other sports have already defined.

That’s our approach. We actually go even farther. We want 200-500 fans at each of 50 matches across 30 cities in the US every weekend, with 1,000-2,000 fans in 15-20 other matches and maybe push 4,000 fans at one or two matches each month. That will allow our athletes, coaches and staff to make money in and from this sport.

If athletes want to make money, the money people have to want to make money

Look at the first two paragraphs in the section above: “commercial viability,” “financial interest,” “want track & field athletes to make more money.” Ask yourself if some of the people and organizations who write checks to athletes think in the first two terms or actually want the third. All the leagues discussed here are structured and run as commercial enterprises. Businesses. They’re not non-profits, they’re not bankrolled by foundations or floated by grants. Neither are the players. The team and league owners and investors expect some level of financial return over some timeframe. Their involvement with these properties is not tax deductible. It’s very personal for them, but it’s also very business.

Next time you read about some individual’s or organizations 501(c)3 compliant largesse, ask yourself what that money could do – what years of that money could have already done – had it been invested rather than donated. If it went out with the expectation of returning more. If the intent was to render charity obsolete among the ostensibly

RELATED: T&F NEEDS SPORTS BUSINESS PROFESSIONALS, PART II

Again, as always, just like other sports do. The successful ones.

How much should track & field athletes expect to make?

The estimate of ~$50,000 from the graph towards the top applies to those athletes competing at World Championships. A few paragraphs ago, we said we want 50-70 matches every weekend. That will require a lot of athletes, none of them at World Championships level and few at USA National Championships level. How much should they get paid?

Go to the bottom left of the graph. Then go down and to the left a little more.

MORE: TRYING TO FIND THE PRO ATHLETES AT USA OUTDOOR NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS

Most athletes won’t get paid much, if anything at all. At best, we hope to cover rent. More likely, beer money. And for most athletes, nothing at all. Actually, most athletes may end up paying money for our leagues, just as their friends and peers with similar levels of ability in sports like hockey, soccer, volleyball, basketball and ultimate do. The vast majority of people who play sports recreationally or at a competitive amateur level pay for it. League dues cover things like insurance, facility rental, administration and uniforms. The athletes have to buy their equipment and pay for their transportation. Reaching the point of a per diem, let alone a stipend, is a huge accomplishment.

Track & field athletes and college coaches at all levels need to get over the idea that the athletes must get paid before they pick up a shot or set up a hurdle. No other sport – certainly none of the successful ones – have athlete pay as a minimum expectation. Athletes join leagues for a variety of reasons: love of the game, competitive fever, the social aspect, ambition to see how far they can go.

FAQs: #5: How much do athletes get paid?

The ones who stand to make money from doing it don’t need to go looking for money: it comes looking for them.

All we need are the athletes, and with 20,000 track & field athletes graduating college each year, we know they are out there. We just need you to get in touch with us and tell us where we should set up a team. Like, right now. Tell us.